Another World in Tucson: DeGrazia Gallery in the Sun

“I want to be notorious rather than famous. Fame has too much responsibility. People forget you are human.” — Ettore “Ted” DeGrazia

A week ago, I knew two things about Ted DeGrazia:

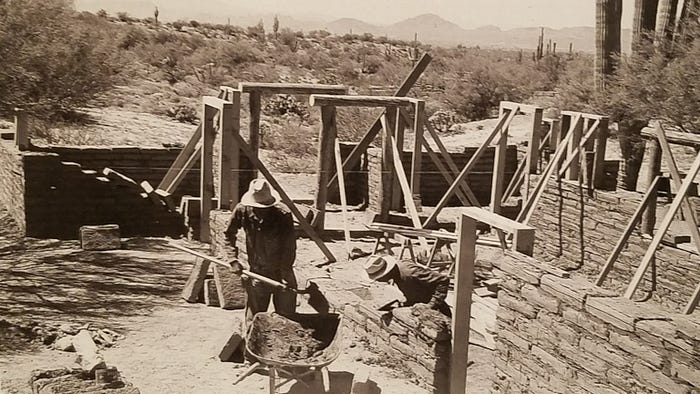

One, in 1949 he bought 10 acres of land ‘way out in the Santa Catalina Foothills, north of Tucson, well beyond city services, no electricity, no water. With the help of Yaqui and Tohono O’odham friends, he first built a chapel, which he called the Mission in the Sun. Then he built a small house for his wife and himself, and the original ‘Little Gallery.’ Finally, in 1965, he completed construction of the rambling 16,015-square-foot DeGrazia Gallery in the Sun, which today is open to the public, showing his artwork in thirteen rooms.

Two, for much of his productive life, art critics dismissed his work as too commercial, and not “serious.” And I thought I agreed with them.

But, after a recent afternoon delighting in “the place that Ted built” — now listed on the National Historic Registry as a historic district — I came away with a changed view of DeGrazia’s work.

Ettore “Ted” DeGrazia (1909-1982) lived life to the max. He was a man with big ideas, a strong will, deep faith, and an open heart — all of which is evidenced in the little personal village he built, and the art he created.

Born in 1909 in a mining town in Arizona Territory (three years before Arizona achieved statehood), his family had immigrated from Calabria and his father and uncles worked in the copper mines. He labored in the mines for a time, too, but later said, “I knew I would be underground all of my life if I didn’t succeed at something else.” So, in 1933, he headed to Tucson with his trumpet, a change of clothes, and $15 in his pocket, to study music and art at the University of Arizona. He played trumpet in a band and did landscaping to pay his tuition.

His first bachelor’s degree was in Art Education, his second was in Fine Arts, and he went on to earn a master’s degree in Art Education. Combining his love of music and visual art, his thesis set forth “a method whereby music can better be understood and appreciated by the projection of its moods and feelings into another dimension.” Indeed, one can see movement and rhythm featured in his art throughout his life.

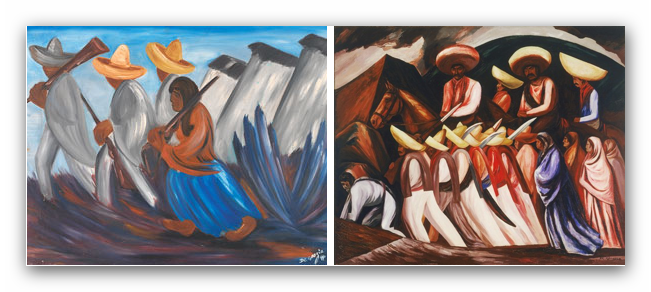

In the early 1940s, DeGrazia apprenticed with Diego Rivera in Mexico City, and also worked with José Clemente Orozco. He absorbed much from these masters, and the surrounding culture, and his early work portrayed cockfights, beggars, workers, and the Mexican Revolution. Rivera and Orozco favored his work, but his dark Mexican-inspired subjects did not bring him the recognition he expected when her returned home.

For years he struggled to earn a living as an artist. The public ignored him, galleries rejected him, and critics dismissed his work. His paintings were selling for only $3 to $5, so he tried his hand at sculpture, pottery, murals, jewelry, clothing — anything to pay the bills. He developed a brilliant copper ceramic glaze. But he continued to paint, and over time his style changed.

He began to use lighter colors and lighter subject matter. He started painting children, horses, the desert Indians. At last his work caught on with the public. He found a lithographer who could reproduce his paintings, and he began to sell them to a wider market at a lower cost.

DeGrazia’s big break came in 1960, when UNICEF reproduced his painting “Los Niños” for holiday cards. Five million boxes of the cards were sold, making DeGrazia the most-reproduced artist in the world.

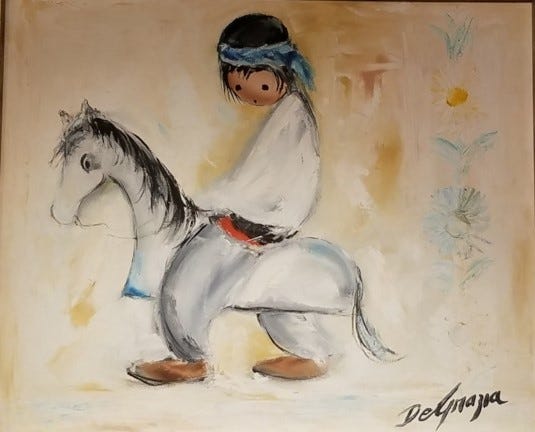

His most successful series was Fun and Games, which features children (and occasionally nuns), kites and carousels and hobby horses. Considered too saccharine by some, the simple expressive lines and poignant subjects had wide appeal. Commercial success for good reason: his art was engaging, uncomplicated, accessible.

DeGrazia was convinced that tribal cultures were vanishing, and he wanted to document them before that happened. Much of his art was influenced by his travels throughout Indian lands in the southwest. Lance Laber, Executive Director of the DeGrazia Foundation, says, “He wasn’t just an artist. He was a historian. He loved history.”

He was a storyteller, too. Not only in paint, but also writing and illustrating books, he portrayed scenes from O’odham legends and the life of Padre Kino.

He painted numerous series, pursuing the subjects that interested him, including bullfights, horses, cowboys. He repeatedly composed his idealized cowboy viewed from behind, a lone mounted rider heading or gazing toward a distant horizon.

DeGrazia once said, “… people say all I do is paint children… [but] I do a lot of drastic paintings where a lot of speed shows in a circle or horizontal.” This interest in movement and energy is nicely demonstrated in one room in which stands his paint-spattered easel. His charming roadrunner series is laid out, from experimental studies of motion to finished paintings, showing his exploration of “speed.”

DeGrazia’s art aside, a visit to “the place that Ted built” is to meander through another world. Rambling adobe buildings, a riotous courtyard garden, inventive decorative touches — the compound exudes creative energy. Have you ever before seen a floor inset with rounds of cholla cactus?

DeGrazia’s Mission in the Sun, built in honor of Padre Kino and dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe, was the beginning of “the place that Ted built,” — and we’ll end with it. The first building he constructed on the 10-acre site in 1949, DeGrazia designed it with an opening in the roof because, in his words, “You can’t close up God in a stuffy room!” The mission is normally open to visitors every day of the year, but a fire in May, 2017 did extensive interior damage and the chapel is now closed off behind chain-link fencing, a tarp over a now-much-larger hole in the roof. Fortunately, the structure did not burn to the ground and—although at least some of DeGrazia’s original murals have been lost — one day the Foundation intends to restore it.

“Because I was born in the southwest, and live there, I live it with a passion. The state has a harsh temperament as though it were alive. It is rough, colorless, and silent. And yet, you feel a gentleness, see beauty, and color in a storm, the skies roar, the cactus of the desert in its prickly silence bursts forth for a moment of exquisite beauty.” Ted DeGrazia